Miles Gertler

& Igor Bragado

Fighting Globesity: A Practical Guide to Personal Health and Global Sustainability, by Phillip Mills and Jackie Mills M.D., has a five-star rating on Amazon. According to one reviewer, “It certainly makes you think about the things you put into your body and simple things you can do to change the world.”

The ultimate frontier of the Anthropocene might well be the human body. Or so it seems, according to a freshly available arsenal of fitness regimens, survival guides, academic reports, news media, and cultural products, which demonstrate an impulse to connect the fitness of the body with its capacity to resist climatic failure.

Take Pure Advantage, an environmental research and lobbying group founded by fitness mogul Phillip Mills, who argues that the fitness of the individual is a critical component in global environmental health. Mills funded documentaries like The Human Element, which explores people’s relationships with climate change, and his fitness program Les Mills, which is “on a mission to create a fitter planet” and marries strength conditioning with the construction of virtual terrains like The Trip, described as “a completely new cycling experience using digital projection to create new worlds.” The Les Mills website declares, “The battles to tackle global physical inactivity and prevent climate change are inextricably linked, with neither likely to succeed unless holistic and sustainable solutions can be sought,” and Mills himself told an interviewer, “We have to deal with [climate change] urgently. And it just so happens that a lot of the ways that we can fix it are things that are really good for us, good for our health and good for the environment.” In 2007, Mills published Fighting Globesity: A Practical Guide to Personal Health and Global Sustainability, and he’s not alone in claiming the resilience of the body as a lifeboat to counter the instability of the planet.

#newfrontiers

If the Anthropocene represents an existential threat, then it is somewhat paradoxical that, faced with the possibility of humankind’s demise, the individual body is more present than ever. A focus on the body that prioritizes individual performance and status seems out of place at a moment when the well-being of humanity is under threat. In cultural discourse, politics, and the popular imaginary, human anatomy is more visible and available as a subject for modification, regulation, and design than ever before. From the surgeon’s clinic to Facetune, through gut health and biohacking, and from the bedroom to Equinox, the body is under near-constant scrutiny, searching for new sites of value, be it social, material, or otherwise.

As a result, a frontierist attitude has been projected onto the body: an anthropo-frontierism that regards the fitness of the body as a useful technology. Among its proposed uses is to function as a lifeboat, escaping the consequences of planetary environmental collapse in the mode articulated by Les Mills. Anthopo-frontierism mirrors the logic of American frontierism – that is, the Wild West spirit of territorially progressive exploitation and technological development attendant to the feverish pursuit of expansive new terrain, where the survival of the fittest generally superseded collective concerns. In its endless pursuit of resources to exploit, frontierism ultimately produced the carbon paradigm that drives markets today. Frontier individualism and the prioritization of the self are both cause and consequence of the global carbon paradigm and its attendant crises. The consequences of this paradigm have in many ways provoked a call for collective action, but anthropo-frontierism has in parallel articulated an individualized, niche mode of resistance to the cataclysmic at the scale of the body: climate fitness. In other words, as a Les Mills slogan puts it, “Fitter You, Fitter Planet.” If the environment is being degraded, then at the very least the body can be recalibrated to be its very best – better able to mitigate the effects that industrialization and pollution might have caused. Daily life increasingly appears to involve optimizing and defending the body against environmental threats to its most basic functions.

#culturismo

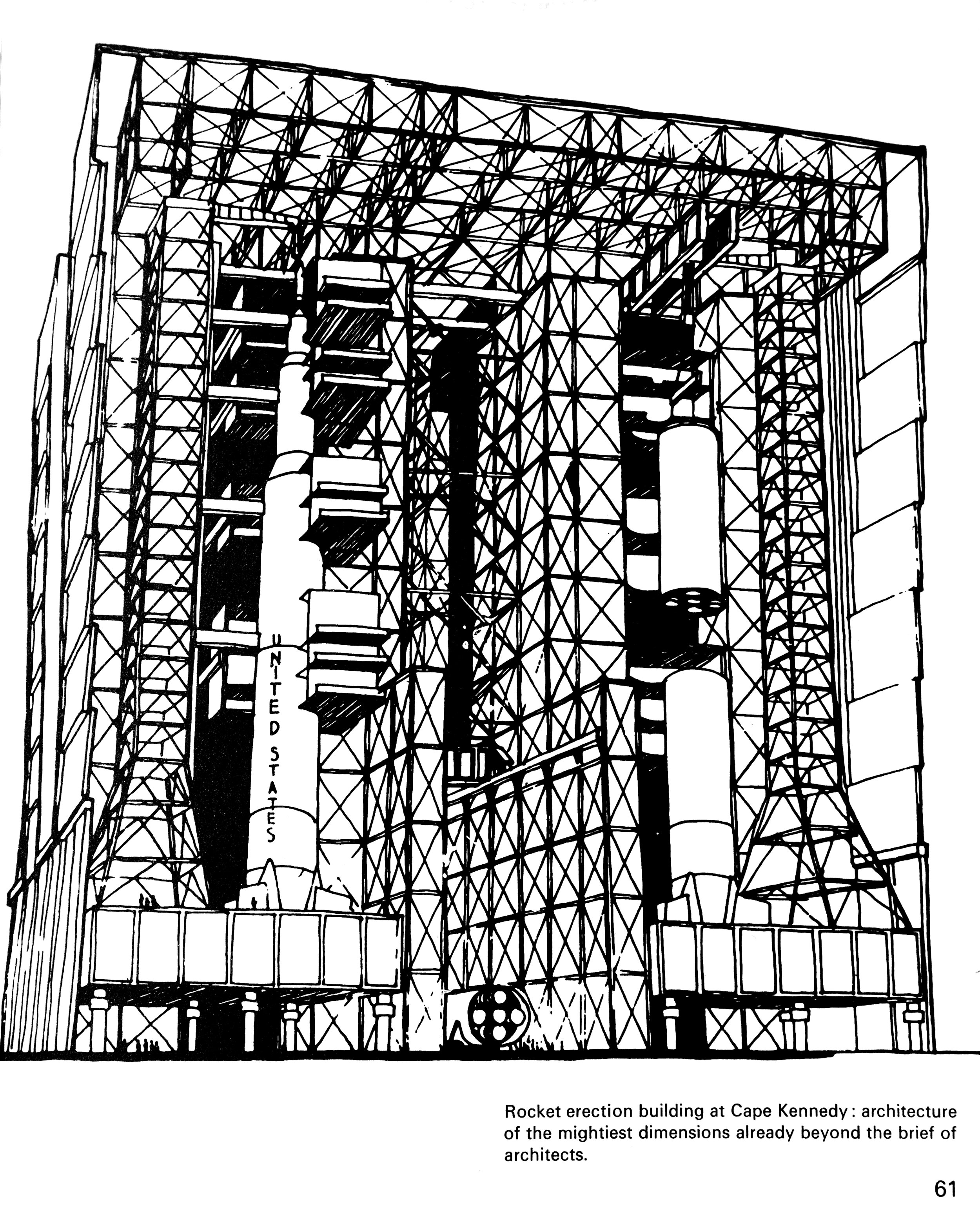

In colonialism, the body was a vehicle to reach the frontier. In the Anthropocene, the body becomes the frontier itself. This change comes from recognizing that the myth of the infinite territory is now suddenly impossible in the context of climate change. But colonialist practices didn’t die, they were transformed, prospecting new terrains for external economic growth opportunities. Climate change itself has changed the location and nature of the “frontier,” reframing fitness as an episodic behavior on the broader spectrums between living and dying, self-construction and deconstruction.

#thepowerofplacebo

If fitness has emerged as a coping mechanism for the prospective extinction of the species, then the behaviors we observe may well become more exaggerated as we approach and pass 2030, when the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says the window for action to prevent irreversible and cataclysmic climate change will shut. With no solution yet emerging to address, let alone solve, the problem at the scale of society, individuated responses may be misdirected and inadequate, yet they demonstrate the necessity of an existential placebo to overcome the mounting anxiety of environmental collapse.

Consider the survival mentality of boot camp fitness programs, the call to training that a nearness to death or illness can provoke, and the explosion of wellness as a luxury product. While the persistence of the species has never looked so uncertain, the promises of life-extending pharmaceutical regimens and cryogenic stem-cell injections guarantee to at least defer your own expiration – if you can afford them.

In his 1990 essay in AA Files, “The Building in Pain: The Body and Architecture in Post-Modern Culture,” Anthony Vidler observed that the subject of the postmodern gym was a body whose finitude was ever in question: fitness alone could not render the body whole. And in many ways, the cultural priority of the gym today reifies Rem Koolhaas’s statement from his essay in Content, “Junkspace,” that “the cosmetic is the new cosmic,” as technologies of self-construction bring the possibility of immortality through the promise of virtual perpetuity and that “cyberspace has become the great outdoors. . . . Is each of us a mini-construction site? Mankind the sum of 3 to 5 billion individual upgrades?” In this context, the #shredded body constitutes a carbon form.

#gymselfie

Of course the ubiquity of digital images encourages the vanity complex. Neuroscientific studies of social media use indicate that vain behavior is rooted in strategies to generally improve the odds of survival. New research suggests that we regularly demand value from sustained engagement with social media, which capitalizes on preexisting social drives. A 2015 report in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, titled “The Emerging Neuroscience of Social Media,” states:

People are driven to connect with others and manage their reputation, and likely derive significant adaptive advantages from doing so. Indeed, finding ways to fulfill our need to belong to a social group may be as important to our survival as fulfilling our basic biological needs, such as obtaining food and sex. Living as part of an interconnected group enhances reproductive success by providing access to potential mates, and enhances physical survival by providing increased safety from potential predators, as well as providing access to the fruits of communal agriculture and cooperative hunting efforts. . . . Groups increase the potential to not only survive, but also thrive.

These “soft” values are made evident at the anatomical scale through the neural responses associated with “social cognition (i.e., mentalizing), self-referential cognition, and social reward processing.”

Dopamine stimulation and serotonin production are signals of positive returns in the landscape of social resource exploration. Since the smartphone is for so many people a prosthetic enhancement, we ought to consider its neural and social consequences as part of the anthropo-frontierist effort. It is certainly a critical agent in today’s arena of self-construction.

#yourenotevenalive

Canadian artist, singer, and producer Grimes has produced an aesthetic project in the ethos of anthropo-frontierism. Grimes, along with boyfriend Elon Musk, is part of a group of superrich and societal elites for whom civilizational collapse is a creative engine. Musk’s SpaceX is a company founded “with the ultimate goal of enabling people to live on other planets,” arguably due to the future uninhabitability of our own, and Grimes’s aesthetic explores the production of images of the augmented self in a mode that tracks with Mark Wigley’s 2001 assertion in the Grey Room essay “Network Fever” that “the evolution of technology is the evolution of the human body.”

Promoting the release of her 2019 album, Miss_Anthropocene – “a concept album about the anthropomorphic goddess of climate change . . . each song will be a different embodiment of human extinction,” she wrote on Twitter in March – Grimes’s own Instagram demonstrated precisely the artist’s aesthetic project as it is enacted through her own body: a form of advanced survivalism through an overload of self-design. In a post from July, which has since been deleted, Grimes, clad in athleisure apparel, cites a new partnership with Adidas as she kneels on a rock and looks toward a menacing sky.

In the music video for “We Appreciate Power,” Grimes gives form to this regimen and literal meaning to the “360 approach.” She variously presents herself and her collaborator, Hana, on a rotating platform, clad in catsuits, their anatomical prowess accentuated as if drawn in manga, further equipped with an arsenal of swords, bows, and guns. Their optimized bodies are exhibited in the round – as a design product – prepared to endure a host of existential threats. Grimes calls for preservation through cosmetics and the image-based, online archive: “Elevate the human race, putting makeup on my face. . . . Come on you’re not even alive, if you’re not backed up on a drive.”

#nolifeboat

In her 2012 Artforum essay “Vanishing Point,” Sylvia Lavin writes, “In the complex ecology that characterizes our contemporary culture of excess . . . evidence of irrelevance instead lies in overproduction and superexposure: A new typology now waxes when it is on the wane.” Facing instability and the prospective destruction of the environment as we know it, the individual has become both ubiquitous terrain and agent of its own colonization. As capitalism’s last terrestrial frontiers are exhausted, its prospective gaze has turned to other domains. The defense of the self from ourselves will undoubtedly continue to be an increasingly complicated problem of daily life. The desire to extract value from the body is necessarily entangled with a new aesthetic of the self that variously celebrates virgin resources where external sources face depletion, and, adversely, systemic escape from the paradigm that resource extraction continues to feed. This attitude inhabits the logic of carbon capitalism itself and exacerbates a preoccupation with the self that may only signal its own demise. It points to an obsession with an aesthetic of the body as a lifeboat, when ultimately none may be available.