Charles Waldheim

“The Aero-Gangplank and the Avant-Garde” written by Charles Waldheim, was published in Log 46, summer 2019.

The British avant-garde of the 1960s and ’70s is often associated with an architecture of autonomy within a context of new societal, environmental, and cultural conditions. Paradoxically, the prospects for a new British architecture in this era were often illustrated by analogy with the infrastructure of American military-industrial technologies. Among these, the humble airplane passenger loading bridge serves as a case study. Devised, developed, and deployed by American engineers and architects working in quiet collaboration, the architectural significance of the passenger bridge was brought to the attention of architects in Europe and North America by British architects who saw the movable structure as evidence of a long-anticipated emancipation from architecture’s spatial fixity. The telescoping loading bridge was received as evidence of a new mobility and mutability associated with a technically enlightened avant-gardism, a reading that invoked new modes of architectural subjectivity and a new role for architecture as a facet of popular culture.

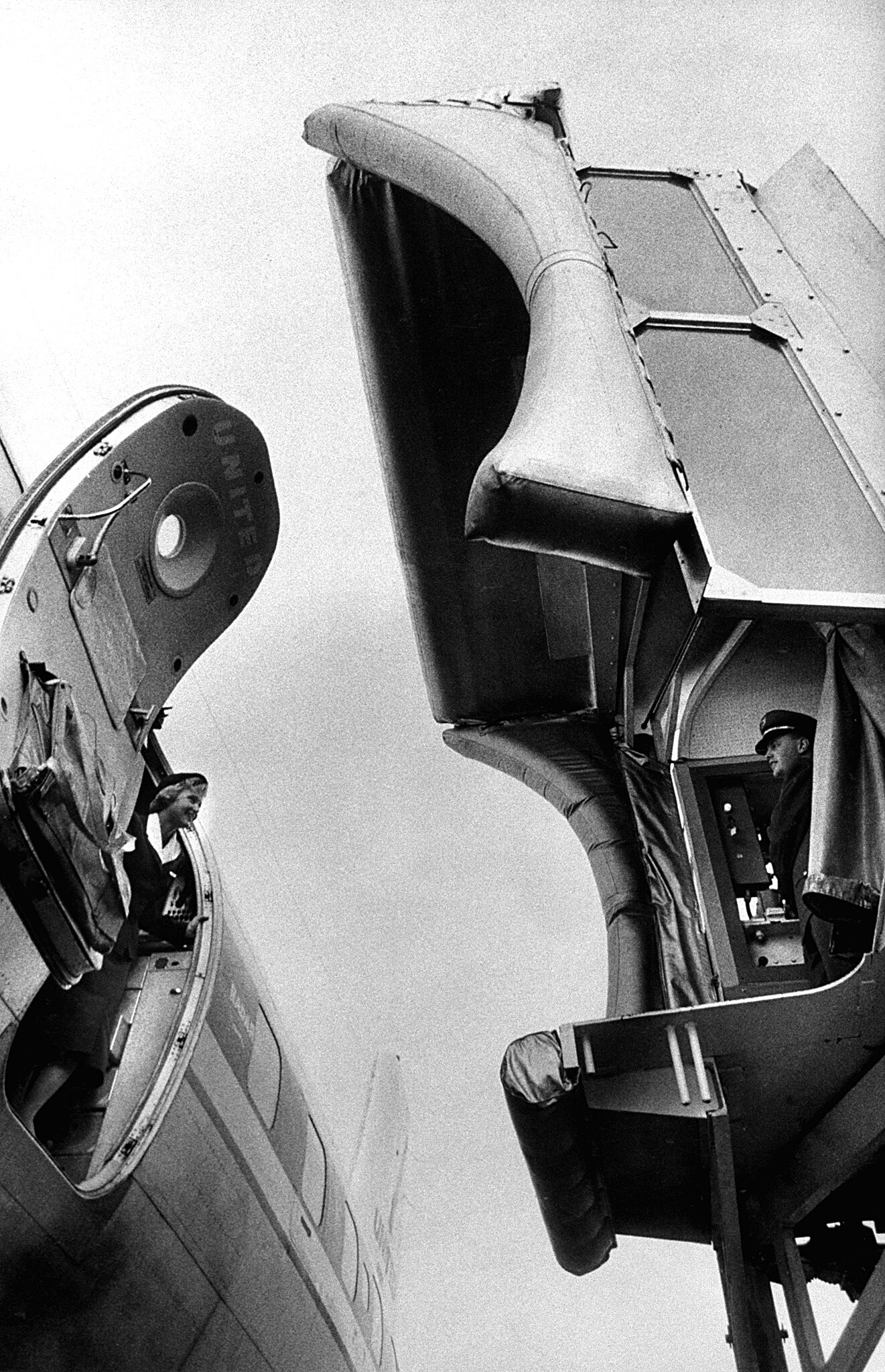

Photographs illustrating Wayne Thomis, “Folding Bridge Used at O’Hare: Public Boards Plane Under Shelter,” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1958. All images courtesy the author.

Instrument of American Engineering

The first enclosed commercial airline passenger loading bridge was deployed at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport on March 28, 1958. The occasion was sufficiently newsworthy to be reported in the Chicago Tribune under the headline “Folding Bridge Used at O’Hare: Public Boards Plane Under Shelter.” 1 The article appeared below two photographs showing the “new gangway” in its retracted and extended positions. United Air Lines first deployed the technology to speed up the turnaround time of flights. While various other techniques had been devised for boarding aircraft from the tarmac, this was the first that allowed passengers to board at the level of the plane’s door without going outside.2 The device was also marketed as an innovation in passenger comfort, as it insulated enplaning and deplaning passengers from the weather – no small measure in Chicago’s winters – although it was primarily developed to minimize the dangers associated with passenger proximity to operating aircraft engines, especially given the recently developed passenger jet.

The aero-gangplank installed at O’Hare, a primitive prototype of the now ubiquitous bridge, consisted of a telescoping enclosed walkway hinged to pivot at an opening at the second floor of the terminal. The airside end of the “folding bridge” included controls for “driving” it and a retractable pneumatic diaphragm designed to nestle gently against the fuselage around the airplane’s passenger door. A motorized electric-hydraulic dolly carried the weight of the bridge on rubber wheels and enabled a circumscribed 120-degree range of movement across the apron. The first bridge was of painted corrugated metal over a steel frame. The interior was finished with painted walls, eye-level windows, ceiling-mounted fluorescent light fixtures, and industrial flooring. At just over 50 feet long when retracted and double that length when fully extended, the gangway proved to be a flexible, efficient, and cost-effective means of loading and unloading commercial aircraft.3 After its successful debut at O’Hare, the aero-gangplank was deployed at a number of airports across the country, and was quickly embraced in the early 1960s as an industry standard for the new jet-age airports.

Chicago-based United Air Lines and many of its competitors anticipated the need for loading bridges to accommodate the expected rapid growth of commercial air travel following World War II. United licensed the technology for the aero-gangplank from Lockheed Air Terminal, Inc., which had developed it in the mid-1950s based on aeronautical engineer Frank Der Yuen’s concept for a loading bridge, which stemmed from his experience with aircraft loading and turnaround times during World War II. Following the license agreement with United, and the successful debut of the bridge at O’Hare, Der Yuen and Lockheed filed patents for the design of the “aero-gangplank” in 1959 and 1960.4 Der Yuen and Lockheed continued to improve upon the design throughout the early 1960s, including moving the drivable dolly wheels toward the aircraft end of the bridge, thereby extending the range of movement to an arc of 180 degrees.

The earliest plans for the development of O’Hare in the postwar era were devised by Chicago engineer and parks district executive Ralph Burke, whose 1948 design of the terminal anticipated the installation of “articulated bridges” to provide covered passageways at the second level for boarding and deboarding aircraft.5 While that aspect of Burke’s plan went unrealized for over a decade, the election of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley in 1955 accelerated work at O’Hare. Daley immediately formed the so-called top committee of airline executives to push for O’Hare’s development, and replaced Burke with local architect C.F. Murphy, who was offered the single largest public works job in Chicago over drinks at the Irish Fellowship Club. Murphy had never designed an airport, but he had successfully completed a controversial lakefront water filtration plant on Chicago’s near north side.6

“Airport’s Mobile Covered Bridge,” Life, April 21, 1958. Photo: Al Fenn.

Frank Der Yuen and Francis B. Johnson, assignors to Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. Aero-Gangplank. U.S. patent #3,060,471, filed July 27, 1960; issued October 30, 1962.

The first enclosed commercial airline passenger loading bridge was deployed at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport on March 28, 1958. The occasion was sufficiently newsworthy to be reported in the Chicago Tribune under the headline “Folding Bridge Used at O’Hare: Public Boards Plane Under Shelter.” 1 The article appeared below two photographs showing the “new gangway” in its retracted and extended positions. United Air Lines first deployed the technology to speed up the turnaround time of flights. While various other techniques had been devised for boarding aircraft from the tarmac, this was the first that allowed passengers to board at the level of the plane’s door without going outside.2 The device was also marketed as an innovation in passenger comfort, as it insulated enplaning and deplaning passengers from the weather – no small measure in Chicago’s winters – although it was primarily developed to minimize the dangers associated with passenger proximity to operating aircraft engines, especially given the recently developed passenger jet.

The aero-gangplank installed at O’Hare, a primitive prototype of the now ubiquitous bridge, consisted of a telescoping enclosed walkway hinged to pivot at an opening at the second floor of the terminal. The airside end of the “folding bridge” included controls for “driving” it and a retractable pneumatic diaphragm designed to nestle gently against the fuselage around the airplane’s passenger door. A motorized electric-hydraulic dolly carried the weight of the bridge on rubber wheels and enabled a circumscribed 120-degree range of movement across the apron. The first bridge was of painted corrugated metal over a steel frame. The interior was finished with painted walls, eye-level windows, ceiling-mounted fluorescent light fixtures, and industrial flooring. At just over 50 feet long when retracted and double that length when fully extended, the gangway proved to be a flexible, efficient, and cost-effective means of loading and unloading commercial aircraft.3 After its successful debut at O’Hare, the aero-gangplank was deployed at a number of airports across the country, and was quickly embraced in the early 1960s as an industry standard for the new jet-age airports.

Chicago-based United Air Lines and many of its competitors anticipated the need for loading bridges to accommodate the expected rapid growth of commercial air travel following World War II. United licensed the technology for the aero-gangplank from Lockheed Air Terminal, Inc., which had developed it in the mid-1950s based on aeronautical engineer Frank Der Yuen’s concept for a loading bridge, which stemmed from his experience with aircraft loading and turnaround times during World War II. Following the license agreement with United, and the successful debut of the bridge at O’Hare, Der Yuen and Lockheed filed patents for the design of the “aero-gangplank” in 1959 and 1960.4 Der Yuen and Lockheed continued to improve upon the design throughout the early 1960s, including moving the drivable dolly wheels toward the aircraft end of the bridge, thereby extending the range of movement to an arc of 180 degrees.

The earliest plans for the development of O’Hare in the postwar era were devised by Chicago engineer and parks district executive Ralph Burke, whose 1948 design of the terminal anticipated the installation of “articulated bridges” to provide covered passageways at the second level for boarding and deboarding aircraft.5 While that aspect of Burke’s plan went unrealized for over a decade, the election of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley in 1955 accelerated work at O’Hare. Daley immediately formed the so-called top committee of airline executives to push for O’Hare’s development, and replaced Burke with local architect C.F. Murphy, who was offered the single largest public works job in Chicago over drinks at the Irish Fellowship Club. Murphy had never designed an airport, but he had successfully completed a controversial lakefront water filtration plant on Chicago’s near north side.6

Murphy appointed his longtime colleague Carter Manny as project architect for the airport and set about poaching the best available talent from more prominent Chicago offices, including the Office of Mies van der Rohe and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Manny and his team favored a very different concept for boarding aircraft, the mobile lounge, which was being developed as an alternative to the passenger loading bridge for numerous jet-age airports across the US. Many architects favored the mobile lounge for its elegance and relatively light impact on their architectural ambitions for the airport terminal itself. By contrast, the passenger loading bridge was seen as lacking in aesthetic qualities, subjecting terminal buildings to all manner of distasteful attachments and appendages.

Eero Saarinen, for example, adopted the mobile lounge as the preferred mode of aircraft loading for the sculptural form of his Dulles Airport in Washington, DC. Murphy and Manny lobbied for the mobile lounge at O’Hare as well, but they were obliged to adopt the technology preferred by the airlines and, by extension, the mayor, who depended on the airlines for financing the project.7 Nonetheless, they produced the definitive jet-age airport and the most important innovations in airport design and planning in the second half of the 20th century. O’Hare quickly emerged as the industry standard internationally and was the subject of both popular and professional acclaim, while the vast majority of airports that had adopted the mobile lounge abandoned it as an unsustainable, architectural indulgence. Precisely because of its brute efficiency and obvious technical advantages, the folding bridge was forced upon architects in a situation least able to resist it. Thus the potentially progressive aspects of this hybrid monstrosity – half building, half vehicle – were obscured in favor of a narrative of profitable practicality, at least for American audiences.

United Air Lines DC-8 jets parked at tandem aero-gangplank loading bridges, San Francisco International Airport, circa 1962.

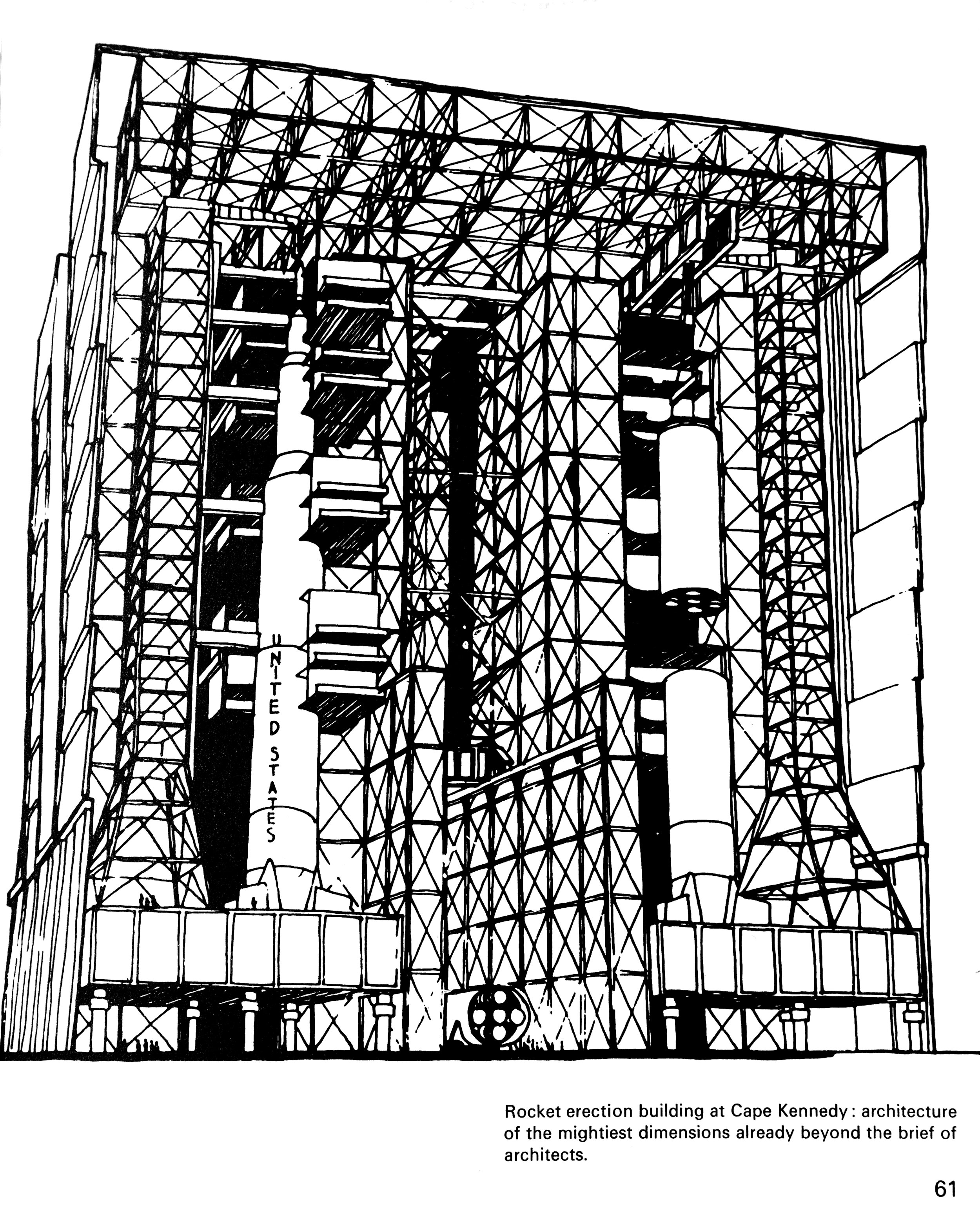

NASA’s Vertical Assembly Building (VAB), Cape Kennedy, Florida. From Peter Cook, Architecture: Action and Plan, 1967.

Evidence of a New British Architecture

In the early 1960s, several images of loading bridges were published in British architectural journals. The October 1962 issue of Architectural Review covered various aspects of the new jet-age airport.8 In “The Obsolescent Airport,” Reyner Banham imagined the airport’s inevitable obsolescence as a strategy for an architecture of impermanence. While offering a lucid account of the impossibility of planning for the unprecedented speed and scale of the jet-age airport, rather than despair at the impossibility of keeping pace with rapid technological change, Banham found the airport to be a site for imagining an architecture of mutability and change rather than stability and permanence. The November issue featured Michael Brawne’s article “Airport Passenger Buildings,” in which he offered a survey of international trends in airport design, claiming the airport terminal as one of three new building types that British architects were experimenting with in the mid-20th century. It was illustrated with photographs of loading bridges at airports in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.9

By the late 1960s and early ’70s, a number of British architects, including Banham, Peter Cook, and Alvin Boyarsky, were making explicit reference to the “folding bridge” in various publications. Often they claimed the American invention as tangible proof of the potentials for an avant-garde architecture based on change and spatial transformation over time. Equally often, their references were deployed in support of a generalized interest in an architecture of plug-ins, clip-ons, and snorkels.10 In appropriating the prosaic passenger loading bridge, British architects associated a practical product of American military-industrial engineering with social transformation and technological enlightenment.

In his 1965 essay “A Clip-On Architecture,” published in Design Quarterly, Banham locates the origins of British architectural interest in obsolescence and mobility in the concept of indeterminacy.11 He cites American architect Gerhard Kallmann’s essay “Towards a New Environment,” which had run in the December 1950 issue of Architectural Review, as the origin for this particular line of thinking, which would inform 15 years of British architectural thought.12 Equally significant for Banham’s idea of a clip-on architecture was Alison and Peter Smithson’s articulation of a cell serviced by attendant infrastructure. Taken together, the ideas of indeterminacy and cellular elements informed not only Banham but also British architectural interests in the 1960s in general.

In his 1967 book Architecture: Action and Plan, Peter Cook juxtaposed the aero-gangplank with the more politically charged and heroically large mobile gantry cranes servicing the US space program’s rockets. His caption for a drawing of the cavernous Vertical Assembly Building, or VAB, designed for the assembly of Apollo rockets at Cape Kennedy, Florida, refers to the “rocket erection building” as “architecture of the mightiest dimensions already beyond the brief of architects.”13 Linking the everyday airline passenger loading bridge with the Saturn V rocket gantry cranes acknowledged both as products of America’s Cold War aerospace-industrial complex, the technical artifacts of which also came to embody the aspirations of a generation of British architects imagining the liberating effects of mutability and obsolescence, assembly and disassembly. The military-industrial images came to represent the potential of constructivist, metabolist, and other progressive architectural projects stemming from very different cultural politics.

Cook claimed the loading bridge as the logical extension of the psychology of movement and an architecture bursting at its limits. An aerial photograph of the United Air Lines terminal in San Francisco International Airport, which Brawne had featured in his survey of airport terminals, showed an impressive radial array of 10 aero-gangplanks simultaneously servicing five United DC-8 jets at their gates. Captioning the photograph “Movable telescopic corridors,”14 Cook situates the air bridges in an eclectic genealogy ranging from the constructivist fantasies of Iakov Chernikhov (1925–33) to Yona Friedman’s Spatial City (1963) to NASA’s VAB (1965). Cook also included his own Plug-in City project (1964) as exemplifying the emancipatory potential of change over time, both physical and psychological, that would characterize much of this period in British architectural appetites.

In his 1970 article “Chicago à la Carte,” Alvin Boyarsky makes explicit reference to O’Hare’s passenger loading bridges as “telescoping passenger snorkels.”15 He situates the loading bridges as essential to the airport’s logic of mobility: “Open-ended, each with its own characteristic realm of geometry, scale, service and information, the automobile, the passenger and the aeroplane are linked.”16

While some British architects were writing about the potential of the passenger loading bridge, others were making or theorizing projects that evoked or depended on analogous movable appendages. Cedric Price’s Fun Palace (1961) and Potteries Thinkbelt (1964–66) projects deployed radially moving circulatory arms and overhead gantry assemblies evocative of the loading bridge. Ron Herron’s Walking City project (1964) imagined a range of telescoping people tubes equally evocative of the loading bridge. In his 1968 book New Directions in British Architecture, Royston Landau surveyed these and other projects for a new architecture and linked Banham’s question of obsolescence to a more general interest in a “plug-in” architecture.17 While Banham claimed to have developed the concept of the “clip-on” as early as 1960, Cook’s “plug-in,” Banham’s “clip-on,” and Boyarsky’s “telescoping snorkels” seem sufficiently of a coherent set in the context of British architectural discourse of the era. Countless distinctions can be drawn between these terms and the concepts they signify, but these architects collectively found the loading bridge to be a heuristic device for conjuring the potential for a radical new architecture capable of reconstituting itself over time. The origins of the loading bridge, however, were far more prosaic and practical than the cultural aspirations suggested by British architectural publications.

Anonymous International Infrastructure

How are we to read the underappreciated passenger loading bridge today? As much as anything else, one is struck by the utter ambivalence with which we regard the once remarkable device. Yet underneath the bridge’s efficiency and ubiquity, it remains utterly undecidable. Is it a building or a vehicle? Is it a conveyance or a device? The mobile bridge represents the hallucinatory capacity of architectural innovation, masked under the cover story of engineered efficiency and optimized rationality. It is among the most anesthetized experiences of contemporary urban life. Rather than invoking the wonder

of the transition from ground to air, the short passage from architecture to airplane is most often unremarkable and accomplished as quickly as possible. The utter banality of the experience is reinforced by its anonymity and ubiquity. They are the same, seemingly, everywhere. Setting aside the occasional whiff of local flavor, wall of humidity, or glimpse outside, the repetitive, undifferentiated, and monotonous transition between earth and sky has had the effect of masking the extraordinary invention that the device represents. The passenger loading bridge was a radical departure from the dominant paradigms of both commercial aviation and architectural culture, but its potential as revelatory of a new architecture has been lost through overexposure and habitual use.

Charles Waldheim is John E. Irving Professor and director of the Office for Urbanization at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Wayne Thomis, “Folding Bridge Used at O’Hare: Public Boards Plane Under Shelter,” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1958, D12.

In 1936, London architect Alan Marlow of Hoar Marlow & Lovett developed an innovative passenger boarding scheme for the “Beehive” Terminal at Gatwick Airport. Marlow’s circular building featured six radiating gangways at tarmac level covered by retractable canvas awnings. This innovation, and Gatwick’s link to London by underground subway (the first in the world to arrive at an airport), enabled travelers to remain out of the elements for the length of their journey, from the city into the airplane.

“Airport’s mobile covered bridge keeps disembarking passengers dry,” Life, April 21, 1958, 50.

Frank Der Yuen and Francis B. Johnson, assignors to Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. Aero-Gangplank. U.S. patent #3,060,471, filed July 27, 1960, and issued October 30, 1962..

Ralph H. Burke, Master Plan of Chicago Orchard (Douglas) Airport (Chicago: R.H. Burke, 1948), 13. Burke’s plan included both renderings of and text references to the new technology in his report to the City of Chicago: “At the loading positions . . . articulated bridges form covered passageways to allow passengers to pass to and from the airplanes without descending to the ground level and without exposure to the weather.”

Charles F. Murphy, “Oral History of Charles F. Murphy,” interview by Carter Manny, June 1, 1981, comp. Chicago Architect Oral History Project, the Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings, Department of Architecture, the Art Institute of Chicago, 1995.

Carter Manny, “Oral History of Carter Manny,” interview by Franz Schulze, March 6, 1992, comp. Chicago Architect Oral History Project, the Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings, Department of Architecture, the Art Institute of Chicago, 1995.

See Reyner Banham, “The Obsolescent Airport” in “The Landscape of Hysteria,” Architectural Review 132, no. 788 (October 1962): 250–60.

Michael Brawne, “Airport Passenger Buildings,” Architectural Review 132, no. 789 (November 1962): 341–48.

Banham, “The Obsolescent Airport,” 252–53. See also Reyner Banham, “A Clip-On Architecture,” Design Quarterly, no. 63 (1965); Peter Cook, Architecture: Action and Plan (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corp., 1967); and Peter Cook et al., eds., Archigram, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999).

Banham, “A Clip-On Architecture,” 2–30.

Gerhard Kallmann, “Towards a New Environment. The way through technology: America’s unrealised potential,” Architectural Review: Man Made America (December 1950): 407–14.

Cook, Architecture: Action and Plan, 61.

Ibid., 72.

Alvin Boyarsky, “Chicago à la Carte: The City as an Energy System,” Architectural Design Journal 40, no. 12 (December 1970): 636.

Ibid.

See Royston Landau, New Directions in British Architecture (New York: Braziller, 1968).